Why Does This Blog Exist?

Wednesday, August 24, 2011

Keeling Bros., Elmwood, Illinois

Wednesday, August 17, 2011

St. Paul – Chapter XII – Sibley, The Frontierman

The pioneer of progress and achievement. -- Benjamin Harrison

Measuring a man at his true value, not so much from the point of view of great achievement as from that of what he was, General Henry Hastings Sibley was one of the greatest men that ever trod the streets of St. Paul. Of distinguished parentage—his father was Judge Sibley of Detroit, Michigan —young Sibley received a good education in academies, from private tutors, and in a law school. Law, however, had no charm for him.

The unknown wilderness of the West from which stories of high adventure and romance found their wav to the law student's heart made him long for the forest primeval north and west of Detroit. His father sympathized with young Henry and helped him to gain positions in trading houses, where the young man came into intimate touch with the Indian trade beyond the frontier. In 1829 he entered the services of the American Fur Company at Mackinac. Though his duties comprised considerable clerical work, his heart was in the errands he was asked to do at far distant points. It was on these trips through the wilderness that he acquired that skill with rifle, rod, and canoe that established his reputation among Indians and frontiersmen. His worth speedily recognized by the fur company, he was promoted to posts of great responsibility. Sibley, being a young man of thrifty habits, gradually amassed capital which, in addition to what he received from his father, was enough to obtain for himself a partnership in the Astor company, for which he became agent.

So great was the confidence the fur company placed in him that in 1834 he was made manager of the American Fur Company of the Upper Mississippi Valley. From his arrival at Mendota in the fall of 1834 until his death in 1891, "Sibley is," says Folwell," easily the most prominent figure in Minnesota history." In addition to his services in behalf of the fur company, Sibley was persistently drafted by his admiring neighbors and friends for public service. The Indians, half-breeds, Canadian voyageurs, and frontiersmen respected, trusted, and loved him. It is no exaggeration to say that his influence with the pioneer population of Minnesota was greater than that of government officials. Shortly after 1837 the business of the American Fur Company began to decline because of the unfair competition of unlicensed Indian traders who by trickery, particularly the sale of the deadly "firewater," succeeded in obtaining the lion's share of the fur business. Eventually in 1842, the American Fur Company went out of business, selling its interest to a St. Louis concern.

Sibley led many hunting expeditions of Indians and trappers to the north and northwest of Mendota, usually giving his followers a great feast before departure. On one occasion, he entertained with a bounteous feast something like 1,000 Indians, including women and children. In 1841, accompanied by 150 Indian warriors, he headed an expedition to a hunting field about 200 miles from Mendota. On this seventy-day trip his party killed 2,000 deer, 60 elk, many bears, a number of buffaloes, and 6 panthers.

In 1838, Sibley was appointed Justice of the Peace, the first civil office in what is now Minnesota. In 1848, he was elected a delegate to Congress and succeeded in having a bill passed that established the Territory of Minnesota. He was re-elected in 1849 and again in 1850. In 1855, Dakota County elected him a member of the territorial legislature.

After Minnesota had been admitted as a state, Sibley became its first governor. In 1862, he moved to St. Paul, where he continued to reside till the time of his death. In the same year, Governor Ramsey appointed him commander of the militia which was to suppress the Sioux outbreak. He defeated the Indians, released their white captives (about 250, one of whom is still living in St. Paul), and took about 2,000 Sioux prisoners. Of the 303 Sioux condemned to death because of their fearful cruelty, only 38 were executed.

Sibley served in many civic capacities until his death in 1891.

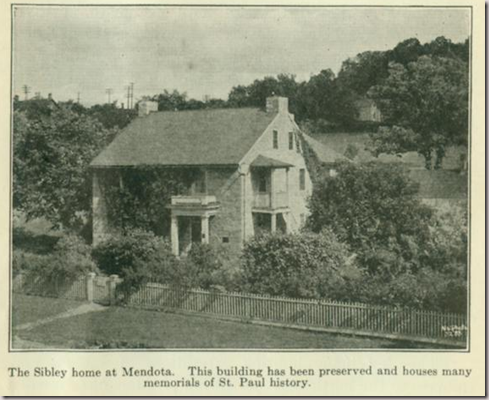

In 1836, Sibley built in Mendota the first residence of stone erected in Minnesota. The building, having been repaired, is still standing and is at present owned (thanks to the generosity of Archbishop Ireland) by the Daughters of the American Revolution. It was in this house that all his children were born. The political boundaries in the eventful years of 1834—62 were so changeable, that each child, though born in the same room, was, strange to say, born in a different political unit, the oldest one in Michigan, the second in Wisconsin, the third in Iowa, the fourth in Dakota, the fifth in the Territory of Minnesota, and the youngest in the state of Minnesota.

It was here also that Sibley entertained, hospitably and lavishly, practically all the distinguished men that visited this section of the country. The more prominent of Sibley's guests were Governor Lewis Cass of Michigan, Major Long of the United States army, Schoolcraft, the explorer of the source of the Mississippi, Jean Nicollet, the explorer of the upper Mississippi and Minnesota rivers, Lieutenant John C. Fremont, the Pathfinder, George Catlin, the noted author of a book on North American Indians, Captain Maryatt, the well-known author of many sea stories, and Governor Ramsay, the first territorial governor of Minnesota. Here, in fact, Sibley lived a happy life till 1862, when he moved to St. Paul.

In 1839, there was a sharp dispute between the United States and Great Britain concerning the Maine boundary. The dispute assumed such a threatening character that public opinion became highly inflamed. The newspapers of the day brought out fiery articles and editorials. In short, the United States and Great Britain were on the brink of war. Congress passed a bill authorizing the enlistment of 40,000 volunteers and granting $10,000,000 for expenses necessary for a military enterprise.

It was just about the time when the relations between the two nations had reached a critical stage that Captain Maryatt was a guest of Sibley at Mendota. Maryatt, who had served in the British navy, became violently abusive of the American claims. The courteous host, never for a minute forgetting his obligations toward a guest, attempted to answer quietly and temperately these abusive attacks. The Britisher, mistaking the genial courtesy of Sibley for cowardice, easy-going tolerance, or lukewarm patriotism, continued ranting about Britain's cause and became actually insulting. He intimated to Sibley that he would show a thing or two to these Yankees when his commission as Commander-in-Chief of the British Naval Forces on the Great Lakes should arrive. Even then Sibley continued to be the affable and friendly host. Maryatt, however, went one step further. While Sibley was in church, Maryatt began to undermine the loyalty of about 60 Sioux warriors, in trying to persuade the Indians that, in case war should break out, they should lift their tomahawks for their "mother-country." After Sibley detected the vicious plot and charged the combative Britisher with his offence, Maryatt stoutly denied his guilt. Sibley, however, had indisputable evidence and politely but firmly requested the Captain to leave his house.

Some of the squatters of the Fort Snelling Reservation who were ejected from the fort in 1840 took various holdings in what now is St. Paul and thus became the founders of the city. Whatever stretches of land they occupied upon the future site of St. Paul they held merely as squatters, as there was no federal land office within reach. When, however, in 1847, the United States government began to survey land west of the St. Croix River and in the vicinity of St. Anthony Falls, the St. Paul pioneers became uneasy as to their titles.

Accordingly, they formed a loose organization and had some 90 acres, including the business part of the village, surveyed and platted, meanwhile awaiting anxiously the opening of a land office at St. Croix Falls. Eventually, in the summer of 1848, the office was opened. Such was the confidence these hardy pioneers had in Sibley that they commissioned him to bid for all parcels of land in his own name and then reconvey them back to the real holders. Practically the whole male population of St. Paul accompanied Sibley to St. Croix Falls. Each settler was armed with a club, and, when the holdings were offered for sale, they watched the bystanders closely, ready, no doubt, to use their primitive weapons, should anybody else, besides Sibley, have the hardihood to offer a bid. Sibley had great difficulties in reconveying the land bought, especially with his French Canadian clients, who firmly believed that their property was safer in Sibley's name than in their own.

In 1849, Sibley, as a delegate to Congress, was successful in having a bill passed that provided for the formation and organization of the Territory of Minnesota. As Sibley was a particular friend of Senator Douglas (of Lincoln-Douglas debates fame), the Illinois senator wished to do a favor to Sibley in proposing to make Mendota instead of St. Paul the capital of the territory. Sibley, however, opposed this proposal and insisted vigorously upon the location of the capital in St. Paul. Here, again, is an instance of the high-mindedness of the man; if he had consented to the change, his real estate holdings in Mendota would have made him a very rich man.

St. Paul was a town of something like 10,000 inhabitants when Sibley moved from Mendota to St. Paul in 1862. He was chiefly responsible for making St. Paul the capital of Minnesota. This event made St. Paul the most conspicuous settlement in the former territory, in giving it the widest publicity at a time when publicity meant life or death to the straggling and struggling pioneer settlements of Minnesota.

St. Paul thus owes much to General Sibley. It seems to have been more within his power than in that of any other man to settle the destiny of this city. Sibley was pre-eminently a Minnesota man and a resident of St. Paul. His sphere of action was necessarily limited to the confines of the state and the city. Even in Congress, though keenly alive to all the big questions of the day, he did not become conspicuous nationally, largely because his heart was in Minnesota. No doubt he had the ability and the personality to play as important a part in national affairs as he played in state matters and municipal problems, but he was by choice and preference a frontiersman. What attracted him and called forth his intense interest was the simple, unaffected life of the trapper, the Indian trader, the half-breed, the full-blood Chippewa or Sioux, and the affairs of the pioneer whites of St. Paul and Minnesota. He shunned, as much as he could, the conventional life of the East and the complicated, intricate problems of national scope. For all that, he was a man, every inch.

QUESTIONS

What moved Sibley to come west?

In what business did he engage?

What kind of man and citizen was he?

How did he treat the Indians?

What political offices did he hold?

What distinguished men visited him?

What bill did he have passed in Congress?

Tell about the treaty he made with the Indians.

How can Sibley be said to be the founder of St. Paul?

Thursday, August 11, 2011

St. Paul – Chapter XI – Fort Snelling

To be prepared for war is one of the most effectual means of preserving peace. - George Washington

Fort Snelling, at the junction of the Mississippi and Minnesota rivers, lies opposite the southwest corner of St. Paul. Half of the bridge over the Mississippi River connecting the city with the fort is within the jurisdiction of St. Paul. Fort Snelling is easily reached by street car and private conveyances, as it is only about four miles from the loop district of St. Paul.

As stated before, the site of Fort Snelling was bought from the Sioux by Lieutenant Pike in 1805. Still, on account of the circumstances mentioned below, it was not till 1819 that the Federal Government took any active steps to erect a military post. Although the Louisiana Purchase and the War of 1812 had put an end to British claims south of the Canadian border, the London government complied reluctantly with the written agreements entered into with the American government. As late as 1815 and later, British influence was almost supreme from Prairie du Chien to the Lake of the Woods, and from Lake Superior for hundreds of miles westward. The profitable Indian trade of this vast region remained in the hands of the Northwest Company, a British concern. During the War of 1812, the company's higher officials were made British military officers. Up to1819 Minnesota, though nominally belonging to the United States, was practically a British dependency.

In the meantime the American Fur Company, founded by John Jacob Astor, had received a charter in 1808 from the state of New York, which charter had been confirmed by the Federal Government, and had accordingly extended its trade area to the upper Mississippi valley. Despite an agreement made by the Northwest Company and the American Fur Company, according to which the Northwest Company was to confine its activities to Canadian territory, well organized smuggling parties of British traders succeeded in selling large stores of goods, including liquors, to the Indians in American territory.

What, however, aroused American feelings particularly was the fact that the British traders were quite successful in undermining the loyalty of the American Indians by gifts and the distribution of British flags and medals.

John Jacob Astor was not slow to take advantage of these conditions in inducing Congress to pass a law in 1816 for the purpose of regulating the American Fur Trade. The chief section of the law provided that "licenses to trade with the Indians, within the territorial limits of the United States, shall not be granted to any but citizens of the United States, unless by the express permission of the President." No doubt Astor was also instrumental in inducing John C. Calhoun, then Secretary of War, to order the establishment of a military post in the upper Mississippi valley.

Pike had bought two strategic tracts of land from the Indians for the purpose of erecting a military post, one at the mouth of the St. Croix, and the other at the mouth of the Minnesota. In 1817, Major Long, who had been sent by Calhoun to select the most suitable of the two sites, chose the one at the mouth of the Minnesota River. This decision' was of great importance both to the city of St. Paul and the state of Minnesota. There is little doubt that, had Long decided in favor of the mouth of the St. Croix, St. Paul would have been located in the same place. The present loop district of St, Paul would then still be the swampy, marshy tract it once was, perhaps the pasture of some farmer whose house would now stand, perchance, where the beautiful State Capitol of Minnesota is. Or, there might have been a village of water-side characters, living on fishing and clamming, where we now find the sky-scrapers of St. Paul. It is, also, highly questionable whether a city located at the mouth of the St. Croix might have been successful in obtaining and retaining the seat of the state government. It is even by no means impossible that St. Paul might have been located in the state of Wisconsin. The bulk of the land bought from the Indians was in the fork of the two rivers and extended a short distance beyond the St. Anthony Falls, including the best residential and business sections of Minneapolis. Westward, the tract usually called Fort Snelling Reservation extended over five miles up the Minnesota River. The reservation spread across the Mississippi to the St. Paul bank of the river, including practically all the district bounded by West Seventh Street on the north and terminating in the northeast about the present Seven Corners of St. Paul. This large tract of land, altogether too extensive for military purposes, was reduced several times. The last reduction in 1871 restricted it to its present area.

In 1810, Col. Henry Leavenworth was ordered to leave Detroit with a troop of about 300 soldiers; cross Lake Michigan to Fort Howard, on Green Bay; take the river route up the Fox River; portage his troops and supplies to the Wisconsin River; proceed down that stream to its junction with the Mississippi; and then canoe up that river to the site selected. It is worth while to relate at least one of the many noteworthy incidents this troop of soldiers under valiant Col. Leavenworth experienced on this long and arduous trip from Detroit to the mouth of the Minnesota. Camping on the shore of Lake Winnebago, Wisconsin, the Colonel, in an interview with the chief of the Indians of this region, asked for permission to pass through his territory. The chief replied, "My brother, do you see the calm, blue sky above us? Do you see the lake that lies so peacefully at our feet? So calm, so peaceful are our hearts towards you. Pass on."

Upon the arrival of Col. Leavenworth at the site selected, he started preparations for the building of the military post.

Upon the arrival of Col. Leavenworth at the site selected, he started preparations for the building of the military post.He selected a place on the right bank of the Minnesota not far from where the village of Mendota now is, cleared the land of timber, built a number of log houses, and surrounded the whole cantonment with a stockade. Considering the available facilities, the quarters provided for the garrison were as comfortable and secure as could reasonably be expected. Because of the friendliness of the Indians of the vicinity, the dwellers of St. Peter's, as the military post was first called, the Minnesota River being then called St. Peter River, were fairly happy and contented.

The first winter, the one of 1819—20, was severe, and the people of St. Peter's suffered considerable hardships. Among the soldiers, scurvy broke out, and about one half of them died. As all medical aid was hundreds of miles away, the small white military establishment was almost in danger of being wiped out. When spring came, the Indians brought large quantities of spignot root (an aromatic, medicinal root, used when dried and ground, most likely the root of meum or baldmoney), which put an end to the dread disease. To prevent a recurrence of this malady, gardens were made, as soon as the weather became favorable, and the abundant supply of vegetables raised put new life and confidence into the survivors. Besides, better and more substantial quarters were erected on the right bank of the Mississippi, about 300 yards west of the present location. This new cantonment was called Fort Coldwater.

The disease of 1819—20 was not only attributable to the lack of suitable food, but also to the villainy of a number of army contractors or their agents, who, in order to lighten the boat loads of supplies, upon leaving St. Louis, poured the brine from the barrels of pork and replaced it with river water.

Col. Leavenworth, to all intents and purposes, made the first permanent settlement of white people in the northwestern wilderness. The place (at St. Peter's), which he first selected as a site for his post, was, taking everything into consideration, perhaps the best possible under the circumstances.

He certainly examined the land carefully and, though observing the magnificent location of the present site in the fork of the two rivers, thought it best, for the time being, to locate his cantonment in the sheltered river bottoms. An examination of the records of the weather bureau vindicates Leavenworth's selection. The present location is perhaps the most exposed place to winds, storms and tornadoes, within 60 miles of the Twin Cities. The builder of this far-flung white outpost, having scarcely gained a foothold in the northwestern wilderness, was called away to other duties. He was succeeded by Colonel Josiah Snelling. He selected the present site, perhaps the most beautiful location of any settlement along the whole course of the great river. He went to work vigorously to establish a suitable and permanent military post, and in this he succeeded so well that, when Major General Winfield Scott inspected the fort in 1824, he was so pleased that he recommended that the name of the fort, which had been known as Fort St. Anthony, he changed to Fort Snelling.

No better place could have been selected for a bridgehead or military fort against invasion or attack. Even in modern warfare it would be eminently suitable for military purposes.

Lawrence Taliaferro was sent by President Monroe in 1819 to this wilderness post as Indian agent. He was an impetuous, ambitious, self-confident man, who, however, for more than twenty years was the highest and most influential civil federal official of the upper Mississippi valley. His policy was threefold:

1. Establishment of peace among the various Indian tribes.

2. Protection of the Indians against aggressive and unfair whites.

3. Promotion of agriculture among the Indians.

On the whole, it must be admitted that he tried very seriously to carry out his policy, but his efforts were doomed to almost complete failure. No doubt he lacked the tact of an administrative officer, and yet it can not be denied that he stood for what was fair and right.

His journals and letters throw a flood of light upon himself and the life and events at Fort Snelling. It was Taliaferro who performed the marriage ceremony of his house servant Harriet Robinson and the famous negro Dred Scott. Reference has been repeatedly made to the reluctance with which Great Britain relinquished her former possessions in the Northwest and her intrigues with American Indians. It is a well-known fact that as late as 1819 the Minnesota Indians were far better acquainted with the British Union Jack than with the Star Spangled Banner, as is evident from the fact that Taliaferro was successful in obtaining the relinquishment by the Indian chiefs of 30 medals of George III, 28 British flags, and 18 gorgets (badges for commissioned officers).

Though Taliaferro tried most earnestly to promote neutrality between the Sioux and Chippewas, he was not very successful in this attempt, as shown by the bloody, treacherous, and entirely unprovoked attack on a number of Chippewas by the Sioux in 1827, scarcely a mile from his own habitation.

In the case referred to, Col. Snelling had to resort to harsh measures to induce the Sioux to surrender the murderers. Upon their being brought in, the captives were surrendered to the Chippewas for punishment. Five of the guilty ones were condemned to run the gauntlet, and thus met their death before a large number of cruel spectators.

In his relations to the white traders, camp followers, and hangers-on, Taliaferro was equally unfortunate. To judge from his words, they must have been highly unscrupulous and offensively dishonest in their dealings with Indians, who were certainly their superiors in all those things that go to make a man. The agricultural experiment Taliaferro tried with Chief Cloudman went scarcely beyond the first stage. Making all kinds of allowances both for Taliaferro's limitations and the meanness of opportunity offered to him, in hissavage environment, we can hardly help saying: ''He tried and failed, but he tried."

Dred Scott, a negro, the plaintiff in the famous Dred Scott Case, the most important slavery case in the history of the United States, was in Fort Snelling from 1836 to'38. Dr. Emerson, an army surgeon, had taken Dred Scott, his slave from Missouri, a slave state, to Illinois, a free state, and afterwards to Fort Snelling then in Wisconsin Territory, a part of the former Northwest Territory which was also free territory. In the fort, as referred to before, Scott was married to Harriet Robinson, also a slave. In 1838, Dred Scott was taken to St. Louis. Suit was brought by Scott to determine whether he could be kept in slavery after having resided in free territory. The case was taken finally to the United States Supreme Court, where it was decided that, being a negro, he was not a citizen. This decision left him in slavery and without recourse.

The decision was almost startling. It tended to strengthen both North and South in their convictions in regard to slavery and made it evident to the North that war would be inevitable.

There were several other important national events with which Fort Snelling was more or less intimately connected. Also, it should not be forgotten that some commandants of the fort, later on, gained a national reputation. Certainly, Lieutenant Colonel Zachary Taylor did not dream of ever occupying the White House, when, in the winter of 1829-30, he looked over the ice-bound Minnesota River and saw the dreary white wilderness at his feet. Nor did the trim Captain Tecumseh Sherman ever think of becoming the second in command of the military forces of the United States, when he was sentencing a half-breed soldier at Fort Snelling to two weeks in the guardhouse for violation of military regulations.

The old round tower and the blockhouse are still standing and are preserved for their historic interest.

Here are still maintained Infantry, Artillery, Cavalry, and modern auxiliary equipment. The site is being constantly improved. The new bridge leading from the fort to the Mendota side of the Minnesota is a marvel of constructive art, enhancing the convenience and appearance of a situation already beautiful.

QUESTIONS

What was the first name of this fort?

Who nave it its present name?

How large was it formerly? How large now?

What bearing did the fur company have on Fort Snelling?

Who chose the present site for this fort?

What hardships were sundered by early settlers?

Why is this a good situation for a fort?

What trouble arose between the Indian tribes?

With what national events and men has the fort been connected?

Wednesday, August 3, 2011

St. Paul–Chapter X–Zebulon M. Pike

(From “St. Paul Location-Development-Opportunities” by F. C. Miller, Ph. D., Webb Book Publishing Co., St. Paul, Minnesota, 1928)

What he greatly thought he nobly dared. – Homer

Soon after the United States had purchased the province of Louisiana from Napoleon, the Federal Government sent out several exploring expeditions into the new territory. The first expedition was headed by Lieutenant Zebulon M. Pike.

Lieutenant Pike ascended the Mississippi River and on September 21, 1805 arrived at the Site of St. Paul. He says in a record of his expedition: "Embarked at a seasonable

hour, breakfasted at the Sioux village on the eastside" [of the Mississippi River, now a part of St, Paul). "It" [ the village ] "consists of eleven lodges, just below a ledge of rocks"

[Indian Mounds Park]. "The village was evacuated at the time, all the Indians having gone out to gather wild rice. About two miles above " [ Indian Mounds Park ] "saw three bears swimming across the river, but at too great distance from us to have killed them; they made the shore before I could come up with them. Passed a camp of Sioux of four lodges, in which I saw only one man, whose name was Black Soldier. The garrulity of the women astonished me, for at the other camps they never opened their lips; but here they flocked around us with all their tongues going at the same time. The cause of this freedom must have been the absence of their lords and masters. We made our camp on the big island" [Pike Island] "opposite St. Peter [Minnesota River].

“September 23, 1805. Prepared for the council which we commenced about 12 o’clock. I had a bower or shade made of my sails, on the beach, into which only my gentlemen (traders] and the chiefs entered. I then addressed them in a speech, which, though long and touching on many points, had for its principal object the granting of land at this place

(Fort Snelling], the Falls of St, Anthony, and St. Croix [river] and making peace with the Chippewas. It was replied to by [ three chiefs ]. They gave me the land required, about 100,000 acres [for] $200,000 and promised me a safe passport for myself and any [Chippewa chiefs I might bring down, but spoke doubtfully with respect to peace. I gave them presents to the amount of $200, and, as soon as the council was over, I allowed the traders to pass out to them some liquor, which, with what I myself gave them, was

equal to 00 gallons. In one half hour they were all embarked for their respective villages."

Upon his return from the upper Mississippi, Lieutenant Pike was ordered to lead an exploring expedition through the very center of the territory obtained by the Louisiana Purchase. On this trip, he discovered the well-known mountain giant, called in his honor Pike's Peak. The country through which Pike was traveling being practically unknown, Pike lost his way, wandered into Spanish territory, and was arrested by the Spanish authorities. Upon proper identification, he was promptly released.