Those intrepid and unflinching men

Who knew no homes save ever-moving tents

--Ella Wheeler Wilcox

When white men first came to the vicinity of St. Paul, they found the territory occupied by two powerful tribes of Indians, the Chippewas, occupying, in general, the lands east of the Mississippi, and the Dakotas, or Sioux, occupying the lands west of it.

THE CHIPPEWAS

The Chippewas belong to that great group of Indian tribes called by the early French explorers the Algonquins, who had occupied all the territory on the Atlantic coast from the Gulf of St. Lawrence to the James River in Virginia and extended westward to the Mississippi River and north to Lake Itasca and Hudson Bay.

In their midwestern home the Chippewas lived almost without exception in forests. Their wooded territory was full of lakes and streams. Here, living in tepees and villages, they found food, shelter, and clothing.

Their history is principally a record of wars against those tribes that pressed them from the East and the Sioux who confronted them on the West. Defeated in the East, they were, nevertheless, successful in driving and keeping the Sioux to the West of the Mississippi. The struggle between these two tribes for possession of this immediate site was a bitter one and engendered a lasting hatred. Two scenes of battles, pioneer writers say, arc Battle Creek Park and Mendota.

Like practically all other Indians, the Chippewas lived by hunting, trapping, fishing, and, to a small extent, by raising corn and pumpkins. Within the woods were moose, bear, elk, and deer. Their weapons were bows made of hard wood or bone, sharp stone-headed arrows, and spears tipped with sharp bone points. Animals were trapped or caught in dead-falls, and fish were taken in nets made of the inner bark of cedar and basswood and nettle fibers. Knives were made from the ribs of moose and awls from the thigh bone of the

muskrat.

Clothing was made of furs and hides. Roughly shaped kettles and pots were made of clay. Wigwams were made by bending over and twisting together young trees and covering them with hides. A hanging mat sufficed for a door.

Compared to the conveniences of white people nearly all their tools and implements were very crude. In three respects, however, they have excelled the palefaces. The moccasin, the snowshoe, and the birch-bark canoe could hardly be improved for such a life as Indians lived.

Although harsh and cunning in warfare, the Chippewas were strictly honest and very hospitable. The peaceful stranger was sacred and the best they had was given to him.

When the French explorers came into contact with the Chippewas, they were received with open arms. These explorers and missionaries captured their hearts by kind and considerate treatment. It was only later that adventurers of other nations unfortunately did a good deal to engender in them a hatred against the whole white race.

The coming of the white man had a profound influence on the monotonous life of the Chippewas. They threw away their crude kettles and pots for copper and brass ware. Instead of bows and arrows and spears, they used the gun, the steel knife, and the metal tomahawk. Instead of taking game for use only, the value of the skins of fur-bearing animals became an incentive to become butchers and trappers. Vast numbers of animals were killed.

Changes were also made in then manner of dress and in their personal habits. Firewater became a curse. Diseases that had been unknown were now contracted. And yet in many respects the white man exerted a beneficial influence.

The Indians were taught mercy and charity; and churches, schools, and hospitals were provided for them. The government also, for the most part, gave them very fair treatment. In the short space of a generation, however, it could not be expected that they should make the same progress which it had taken centuries for the white man to make. In the struggle between the two races they were destined to failure to keep pace with the trend of civilization and were gradually removed to reservations.

The treaty of Fort Snelling, made in 1837, provided that a large part of their lands east of the Mississippi should be ceded to the federal government. In 1847 another treaty was made by which more lands were ceded. Henry M. Rice, former U. S. Senator, of St. Paul, was one of the commissioners who induced the Indians to sign this treaty. In other treaties they disposed of all their lands and they were placed on reservations in the northern part of the state.

Hole-in-the-Day was one of the most prominent Chippewa chiefs. In 1851 he addressed a public meeting in St. Paul and complained bitterly of the wrongs he believe that his

people had suffered. He charged that they had to go too far to receive their money and that poor food producing disease had been dealt out to them.

The following is taken from this speech.

"Though we have sold the greatest portion of our lands, we have gained nothing by it. We are poorer than ever. The more treaties we make, the more miserable we become."

The chief family names of the Chippewas were Loon, Bear, Crane, Martin, Catfish, Wolf, Kagle, Rattlesnake, Goose, Lynx, Cormorant, Beaver, Reindeer, and Merman.

THE SIOUX

During the early days of St. Paul the Sioux, or Dakotas, lived on the west side of the Mississippi. They were a very large tribe, occupying the vast area from the upper Mississippi to the Rocky Mountains. They regarded themselves as the most powerful Indian nation. Indeed, they were of the opinion, before their chiefs hail visited the Great Father at Washington, as they were accustomed to call the President, that the United Dakota nation, under the leadership of their best war chiefs, would prove more than a match for the white invaders.

The territory in which they lived, unlike that of the Chippewas, was almost free of timber except near watercourses and in the foothills of the Rockies. The Sioux in this region were, therefore, aptly named Prairie Indians.

Before these Indians disposed of their lands to the government they lived almost exclusively by hunting and fishing and on wild plants, berries, fruit, deer, buffaloes, wild ducks, and geese. In swampy regions and shallow lakes and river bottoms they gathered wild rice.

It was a unique custom when an Indian chief or his head men visited another settlement for the resident chief to serve dog meat as a delicacy out of respect for his guests. The Sioux had summer houses and winter houses. The summer house was a rude structure made of bark supported by a framework of poles. When they secured their supply of meat they built winter tepees of buffalo skins. About twelve poles formed the framework which was covered with eight buffalo skins, fastened together with sinews. The floor was covered with hay on which buffalo robes were spread. Such a tepee was comfortably warm even in the coldest weather.

It was a unique custom when an Indian chief or his head men visited another settlement for the resident chief to serve dog meat as a delicacy out of respect for his guests. The Sioux had summer houses and winter houses. The summer house was a rude structure made of bark supported by a framework of poles. When they secured their supply of meat they built winter tepees of buffalo skins. About twelve poles formed the framework which was covered with eight buffalo skins, fastened together with sinews. The floor was covered with hay on which buffalo robes were spread. Such a tepee was comfortably warm even in the coldest weather.Their axes and knives were made of stone. Their arrows and spears were headed with deer horn, stones, and the white ligament of the neck of the buffalo, which became hard like iron. The tough skin from the neck of the tortoise furnished bowstrings.

They cooked their food in earthen vessels which they made, or placed it on skin or bark in a hole in the ground where it was cooked by means of heated stones. The stomach of the deer was used for carrying water, fish bones served for combs, and a bone from the forearm of a small animal was used as an awl.

In pottery, the Sioux women did superior work. They also produced works of art in ornamentation and weaving. They made yarn from the tough outer coating of nettles or from bass wood hark which had been softened by boiling.

Custom and public opinion were their only laws. They, too, like the Chippewas were affected with some of the white man's vices, but were sharers also in many of his efforts to assist them to a better life.

The principal treaty with these Indians was made in 1851. They had a magnificent rich empire that was eagerly coveted by the whites. The lands given up consisted of nearly twenty-four million acres of the most fertile land in the Mississippi and Minnesota valleys. For this immense territory a little more than $3,000,000 was agreed to be paid, something like twelve cents an acre. The Indians were to be paid in annuities.

On the announcement of the signing of this treaty, The Pioneer of July 31,1851, said: "The news of this treaty exhilarates our town. It is the greatest event in the history of the territory. We behold now clearly the red savages vanishing, and, in their place, a thousand farms, waving wheat fields, villages and cities, and railroads with trains of cars rumbling afar off."

Thus they, too, were compelled to fall back before the advance of civilization, and, like the Chippewas, to find their home on government reservations. It was too much to expect that they could be assimilated. No hunting tribes can withstand the coining of agriculture. An Indian family needs something like sixteen square miles to make a living, while a white family can do so on forty acres.

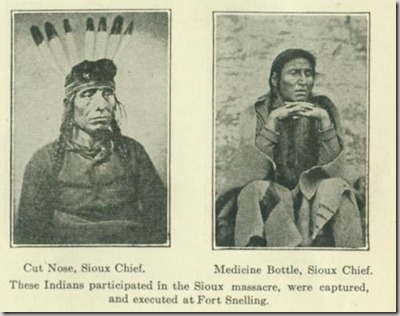

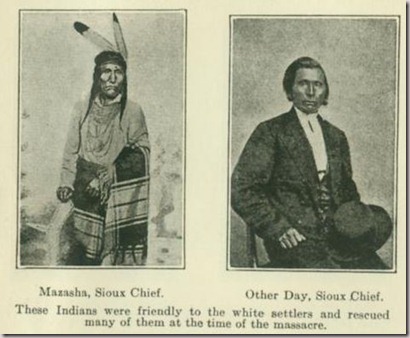

Wabasha and Little Crow were two of the most conspicuous Sioux chiefs.

Except for a few names of towns, streets, and lakes nothing remains from the Indian occupation. Practically their only impression was that which they made upon their own times.

Their lot was inevitable. Walt Whitman says:-

“I see swarms of stalwart chieftains, medicine men, and warriors,It is, however, gratifying that with only rare exceptions they were treated fairly by the whites and the government. Nothing reflects more credit upon St. Paul than the fact that her leading pioneer settlers, such as Ramsey, Kittson, Sibley, Rice, Neill, Marshall, and others were firm friends of the Red Man. Both as private citizens and as officials they did everything in their power to deal justly and fairly with the Chippewas and the Sioux. They frowned on all efforts of unscrupulous whites who regarded the Indians as legitimate prey. When their personal influence was insufficient, they used the force of the law to protect them. In cases of want and distress they helped with food, clothing, and care.

Ah, flitting like ghosts, they pass and are gone in the twilight."

They even made efforts to educate them and to train them in the culture of crops and other fundamentals of white civilization.

Even the Indian trader, according to General Sibley, was fair and friendly with the Indians. Sibley says, "The reliance of the savage upon his trader became almost without limit. The white man was the confidant and sharer of his joys and his sorrows and his influence was, therefore, almost boundless, an influence sometimes used to accomplish selfish and unworthy purposes, but more frequently employed for the benefit of the Indian himself." When Indians were sick, the trader often loaned them money and provided care for them.

The Indians themselves have attributed much of their hospitality, or at least the suppression of overt antagonism towards the whites, to the influence of the Christian missionaries who taught them to have mercy and charity. There is no doubt that the doctrine of peace and good will had a good influence on their attitude and conduct. Less bloodshed was the result. But the common occupation of the same territory by whites and Indians was impossible. The modes of life and the ambitions of the two peoples were too different to exist together. The consequence was that the Red Man had to withdraw. It was a repetition of the world-old principle of supremacy by the superior nation. More and more the Indians were compelled to retreat before the on-coming of civilization. They became wards of the government, living on reservations and in a less natural environment. Their numbers have, therefore, gradually diminished. A few of each of these tribes are, however, still living in St. Paul.

QUESTIONS

Why were these two tribes enemies?

How did the lands they occupied affect their life?

What causes account for their passing away?

Where can you find some Indian relics?

Write a story about them.